Hubble captures a dozen Sunburst Arc doppelgangers

Astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have observed a galaxy in the distant regions of the Universe which appears duplicated at least 12 times on the night sky. This unique sight, created by strong gravitational lensing, helps astronomers get a better understanding of the cosmic era known as the epoch of reionisation.

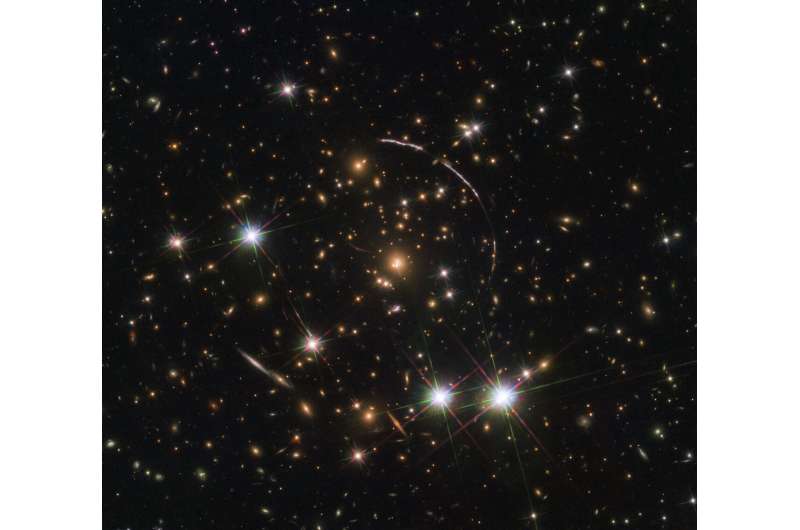

This new image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope shows an astronomical object whose image is multiplied by the effect of strong gravitational lensing. The galaxy, nicknamed the Sunburst Arc, is almost 11 billion light-years away from Earth and has been lensed into multiple images by a massive cluster of galaxies 4.6 billion light-years away.

The mass of the galaxy cluster is large enough to bend and magnify the light from the more distant galaxy behind it. This process leads not only to a deformation of the light from the object, but also to a multiplication of the image of the lensed galaxy.

In the case of the Sunburst Arc the lensing effect led to at least 12 images of the galaxy, distributed over four major arcs. Three of these arcs are visible in the top right of the image, while one counterarc is visible in the lower left—partially obscured by a bright foreground star within the Milky Way.

Hubble uses these cosmic magnifying glasses to study objects otherwise too faint and too small for even its extraordinarily sensitive instruments. The Sunburst Arc is no exception, despite being one of the brightest gravitationally lensed galaxies known.

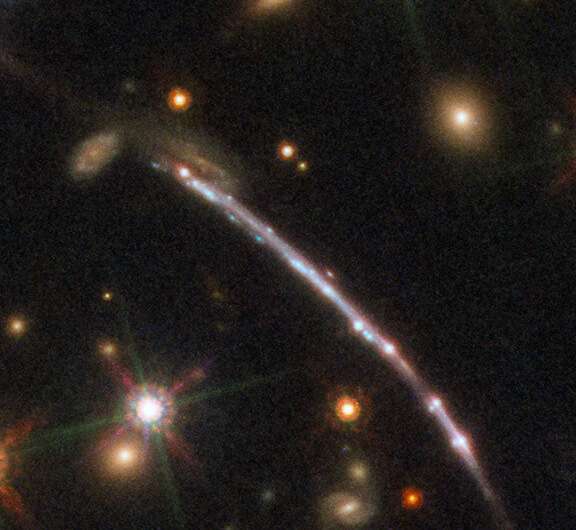

The lens makes various images of the Sunburst Arc between 10 and 30 times brighter. This allows Hubble to view structures as small as 520 light-years across—a rare detailed observation for an object that distant. This compares reasonably well with star forming regions in galaxies in the local Universe, allowing astronomers to study the galaxy and its environment in great detail.

Hubble's observations showed that the Sunburst Arc is an analogue of galaxies which existed at a much earlier time in the history of the Universe: a period known as the epoch of reionisation—an era which began only 150 million years after the Big Bang.

The epoch of reionisation was a key era in the early Universe, one which ended the "dark ages", the epoch before the first stars were created when the Universe was dark and filled with neutral hydrogen. Once the first stars formed, they started to radiate light, producing the high-energy photons required to ionise the neutral hydrogen.

This converted the intergalactic matter into the mostly ionised form in which it exists today. However, to ionise intergalactic hydrogen, high-energy radiation from these early stars would have had to escape their host galaxies without first being absorbed by interstellar matter. So far only a small number of galaxies have been found to "leak" high-energy photons into deep space. How this light escaped from the early galaxies remains a mystery.

The analysis of the Sunburst Arc helps astronomers to add another piece to the puzzle—it seems that at least some photons can leave the galaxy through narrow channels in a gas rich neutral medium. This is the first observation of a long-theorised process. While this process is unlikely to be the main mechanism that led the Universe to become reionised, it may very well have provided a decisive push.

The paper outlining these observations will appear in Science on 8 November 2019.

More information: T.E. Rivera-Thorsen el al., "Gravitational lensing reveals ionizing ultraviolet photons escaping from a distant galaxy," Science (2019). science.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi … 1126/science.aaw0978

Journal information: Science

Provided by NASA